David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas, Ghostwritten) is one of those keystone contemporary writers for me, one to whom I often look for inspiration and reminders that there are still modern writers being published whose work is both challenging and satisfying, intellectual and human, entertaining and philosophically concerned. In short, he's one of those writers who I'd prefer reading one of their lesser works than most other writers' best, because even a faltering David Mitchell is superior and more worthwhile a read than a lot of what's out there these days in the big glut of literary acclaim.

David Mitchell (Cloud Atlas, Ghostwritten) is one of those keystone contemporary writers for me, one to whom I often look for inspiration and reminders that there are still modern writers being published whose work is both challenging and satisfying, intellectual and human, entertaining and philosophically concerned. In short, he's one of those writers who I'd prefer reading one of their lesser works than most other writers' best, because even a faltering David Mitchell is superior and more worthwhile a read than a lot of what's out there these days in the big glut of literary acclaim.To mark the publication of his most recent novel The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, which I have in queue and am working towards dilligently, he gave an interview with Alec Michod for the splendid gift to literary levelheadedness, San Francisco-based Rumpus; in it, he shed a little personal insight on something about which I've thought for a long time: stuttering, speech impediments in general, and how that affects and/or develops a person's linguistic understanding and, to use a writerly phrase, their inner voice, the vocabulary and the speech going on inside our heads and not the one with which we speak. I've always had a sneaking suspicion that growing up with a pretty nasty stutter instilled in me from a wildly young age a deeper appreciation and thoughtfulness about language, how it works and functions as a mechanism for expression, and how important words and communication are, if simply because I had to pay closer attention to words when reading aloud in class or speaking to people, friends, family, strangers. When I knew certain words or parts of words or whole phrases would be difficult for me to get out, I'd have to find ways to navigate around that, by substituting other words, by altering my pronunciation or rhythm to avoid a total, ten-feet-tall obstructing stammer which would not only render me unintelligible but make me look like an idiot. For a young mind, there's something startling and unjustly unfair in realizing that the words in your head cannot match the words springing from your tongue no matter how hard you will them to do so. The words, in a sense, become much more important to a mind tweaked that way. Communication and lack-of-communication (where our words fail) are much more intimately experienced to a mind and a body tuned that way, in a person who deals with those very things per diem. And if the words cannot come out through our lips the way we want them to, well then we have to resolve to find another mode of communicating. When approached by certain words I'm incapable of pronouncing without embarrassment, the easiest thing to do as a kid was expand my vocabulary--find new ways of saying the same thing. It's no surprise a person like this might find solace in the literary arts, the silent and absorbed processing and conveyance of words during which silence is elemental. All of this might even help to explain why, when I'm writing or when I'm reading (i.e. engaged in a nonverbal sort of communique with the author), I'm so excited and alive in a totality that's much more elusive elsewhere. It's the clearest way for for me to communicate, to express myself, and where, at last, the thoughts I'm expressing accord with the thoughts in my head (for the most part). And assuming how we ourselves communicate with others, an exchange of thoughts and ideas, is one of the many processes by which we understand ourself, this can present a problem; if we have an onerous time effectively expressing ourselves or making our desires and sentiments clear to others, a certain crisis of self can result. We are, after all, social animals, part of whose happiness is derived from our interactions with other social animals caught in the same struggle--escaping loneliness, fleeing a permanently confined existence bunkered within our own heads, in which safety is substituted over genuine connection. This, gladly, can be done through verbal or literary dialogues, but my guess says a combination of both is the most satisfying. Reading Dante or Oscar Wilde and speaking with a friend or a stranger about an important topic are two different beasts, both of which are equally important and both of which can, I believe, help inform a person's sense of belonging and community. There's something equal, although different in nature, in feeling a connectedness (which is a form of interfacing in a way) with a thinker from long before you were alive and engaging a living contemporary person in conversation. And if you're talking to a stranger about Dante and Wilde and how they, the historical writers, may have viewed or written about the contemporary world, well now you're just vibrating that big old string of the cello belonging to collective history and playing a wonderful, soaring tune.

The interview takes it in a couple different directions, (much as I've unexpectedly done here with my small bout of self-cross-examination) but it's all highly fascinating stuff--very intriguing to think about.

Mitchell: There’s always the problem of getting what you’re thinking out into the world, isn’t there? I think possibly genes and certainly environment makes us a walking bundle of archetypes, and as a human and as a writer one of my major preoccupations is incommunication. Isn’t it true how everything contains its opposite? How can you have a knowledge of beauty without knowing what ugliness is? Or, or—do you know what I mean? A phenomenon contains its opposite. To have a knowledge of phenomenon is, by default, to know about the opposite. This leads, among other things, to a fascination with words. We aspire to be master communicators, right? But that must also mean we are deeply versed in non-communication, in fluffing it, in getting it wrong, in duff sentences, in not saying quite what you mean and the consequences of that. Stammering makes me an expert in that. I’ve obviously thought about this link a lot, because one of the questions people ask me a lot is “If you hadn’t stammered, would you be a writer?” I think I would have been, but I would have been a different writer. I wouldn’t have had this theme of incommunication. I can identify at least three ways in which they are related. One is—

Rumpus: Stuttering and writing?

Mitchell: You scan the sentences ahead and you see the danger words, the words you won’t be able to say, and then you re-engineer the sentence to be able to go around it. That’s a practical crash course in sentence construction. That, in turn, leads to a practical crash course in register. If you realize you can’t get out the second syllable “less” in the word “useless,” you substitute “futile.” That might fix the vocal problem, but it creates another problem. If you’re amongst a bunch of thirteen-year-old boys, you can’t say a word like “futile.” Everyone will think you’re mad. But again, it’s bloody useful stuff for a writer. You learn your registers. I mean, there they are, all these fancy words, some of them on high registers and others on less educated registers. If you’re a writer and you use a word like “autodidacticism” to describe a character, it completely saves you from having to mention that that character went to college. As a consequence, you develop a higher vocabulary, because you need substitutes.

Rumpus: You need four different words if you can’t say one, for example.

Mitchell: Precisely. I think—I can’t prove it, but I suspect our interior voices are far richer than our spoken voice. If you are one of those people who speak in perfectly mellifluous, complex sentences, I would humbly suggest you think them instead of saying them. It is, of course, impossible to be able to compare a writer’s inner voice and his spoken voice in the quality of the diction and the grammar, but I like to think that stammerers’ inner voices are going to be far more articulate and sharper than someone who isn’t affected by a speech impediment.

Rumpus: Stammering, then, clearly seems to have contributed to your fluency with different voices. Is that why you’re such an apt literary ventriloquist?

Mitchell: I hear what you’re saying, and here’s a new thought for me: perhaps it’s a craftily manifested wish fulfillment on my part. The times I’ve thought I wish I could speak like that guy, or I wish I could chat somebody up unstutteringly. I wish, I wish, I wish—I wonder if that “I wish” is fuel or a kind of power.

I had a close friend growing up who lived next-door. He too had a speech impediment, not a stutter per se but something else a little more sloppily complicated, a fractioned manner of speaking; he spoke fast, as I did then and tend to still do now, and logjammed. We spent whole chunks of time together, baked to leather under the sun, in trees or half submerged in creek water, chomping through a bag of peaches, our chins sticky and sweet, neither one of us concerned about screwing up our words around each other; and while at times I may not have understood what he was saying nor do I believe he always understood what I was saying (at least without asking for him or myself to repeat something) I think we grasped each other on a much more intuitive level. We understood frustrations and confusions and how to deal with them, and we understood patience and maybe leaving room for and being okay with the messiness of language, which is to say we were beginning to understand what it means to be alive.

Check out the interview in full at The Rumpus' website.

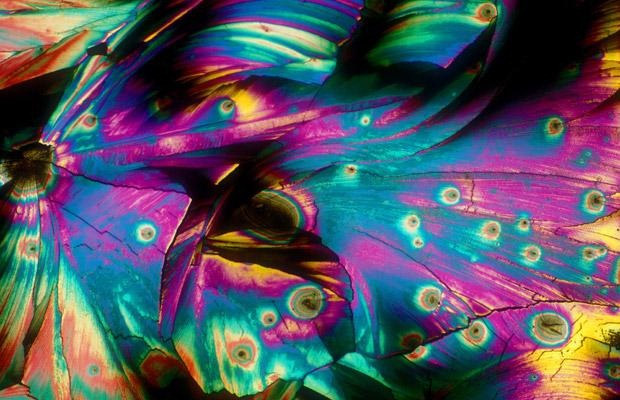

The cinematography and the imagery and the colors in this - not to mention the choreography - were quite literally amazing. Nora's a magnificent artist and a dancer; she plays herself, her mother, and her father, and the performance is consummate. Both of these films are incredibly necessary to watch. It was haunting and touching to watch and listen to these dancers discuss the history (national and continental) they were trying to tackle with some of these films -- genocide, slavery, wars of liberation, violence and injustice, all things the US knows all too well -- and to hear them wrestle with these notions of identity formed through country or nation or by rejecting these ideas; it's what gives this film such verve -- the raw emotion and the brave way these young artists are going about their passions. The central question at the heart of these film is: who is going to speak for Africa? It seems that so often when we hear about Africa we're hearing about it from an outsider, a face in the news. The answer that these films are shouting is "Africa must speak" and these silent, fluid, soft, punishing, excited, loving, angry, brutal, and delicate movements are their words.

The cinematography and the imagery and the colors in this - not to mention the choreography - were quite literally amazing. Nora's a magnificent artist and a dancer; she plays herself, her mother, and her father, and the performance is consummate. Both of these films are incredibly necessary to watch. It was haunting and touching to watch and listen to these dancers discuss the history (national and continental) they were trying to tackle with some of these films -- genocide, slavery, wars of liberation, violence and injustice, all things the US knows all too well -- and to hear them wrestle with these notions of identity formed through country or nation or by rejecting these ideas; it's what gives this film such verve -- the raw emotion and the brave way these young artists are going about their passions. The central question at the heart of these film is: who is going to speak for Africa? It seems that so often when we hear about Africa we're hearing about it from an outsider, a face in the news. The answer that these films are shouting is "Africa must speak" and these silent, fluid, soft, punishing, excited, loving, angry, brutal, and delicate movements are their words.